library(tidyverse)

library(broom.mixed)

library(brms)

library(knitr)

set.seed(55432)

# list of files

dir1 <- "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/avehtari/ROS-Examples/master/ElectionsEconomy/data/hibbs.dat"

# EXAMPLE 1: GDP GROWTH AND ELECTION VOTE SHARE

# quick simple example, using bayes for a linear regression

# what is the impact of economic growth on incumbent vote share?

election <- read_delim(dir1, delim = " ")

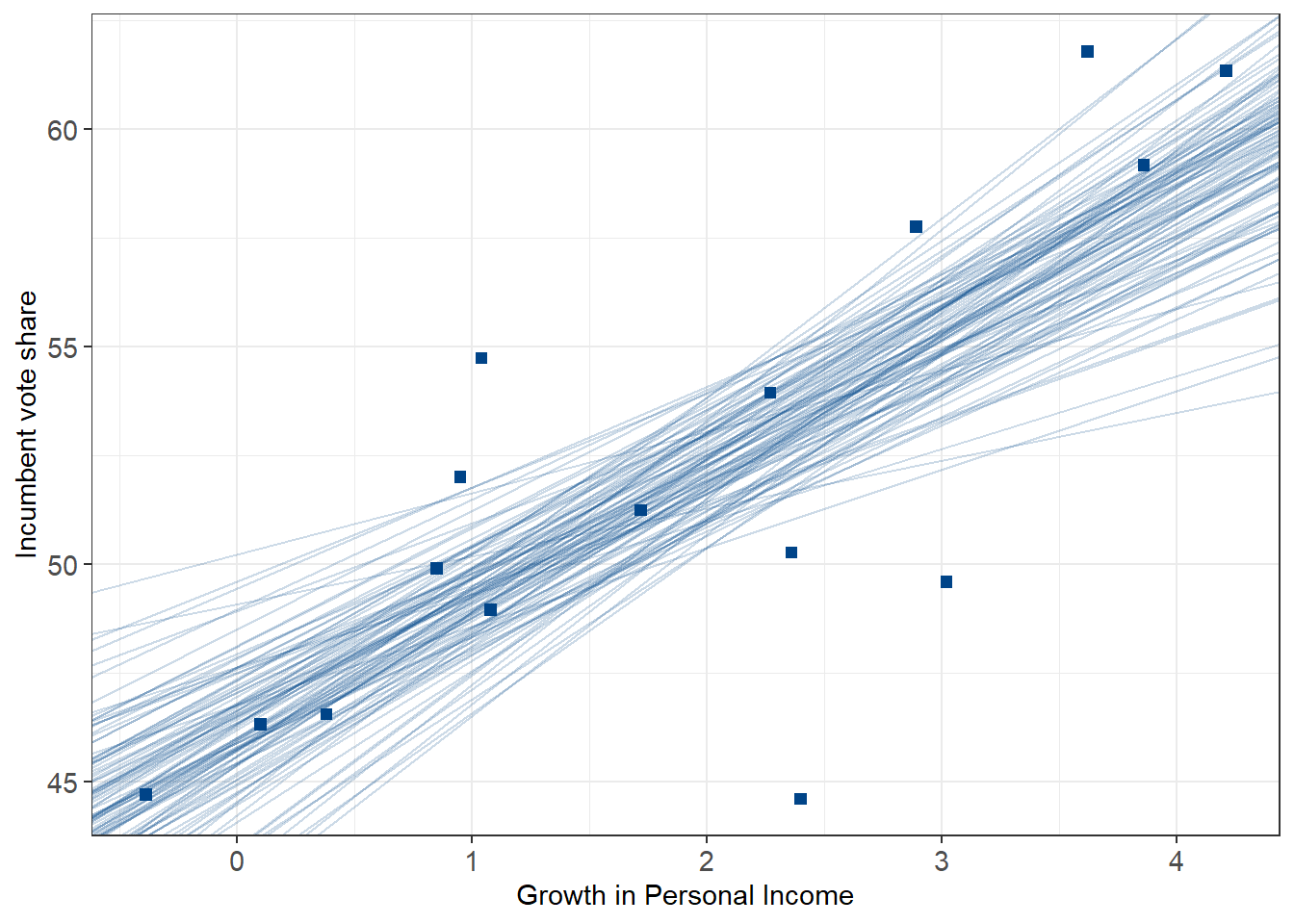

# plot 100 simulations from the posterior

plot_posterior <- function(fit){

M <- as.matrix(fit)

sims <- 100

sims_idx <- sample(1:nrow(M), size=sims)

model_sims <-

M[sims_idx, ][, c(1, 2)] %>% data.frame() %>% setNames(c("intercept", "slope"))

plot1.1 +

geom_abline(data=model_sims, aes(slope = slope, intercept = intercept), alpha = .2, color = '#004488')

}

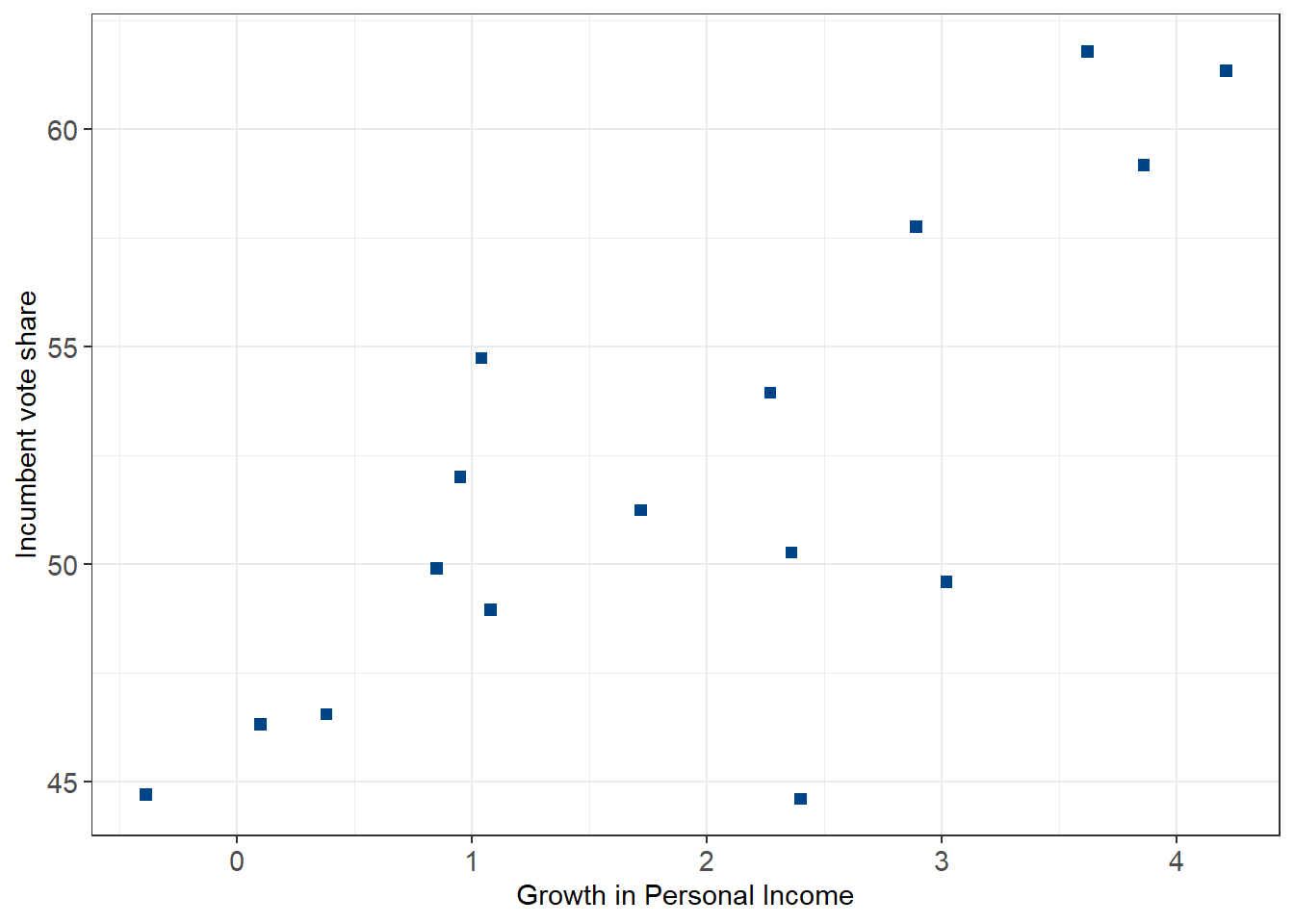

plot1.1 <-

ggplot(election) +

geom_point(aes(x = growth, y = vote), size = 2, shape = 22, fill = '#004488', color = '#004488') +

labs(x = "Growth in Personal Income", y = "Incumbent vote share") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.text = element_text(size = 11))

plot1.1

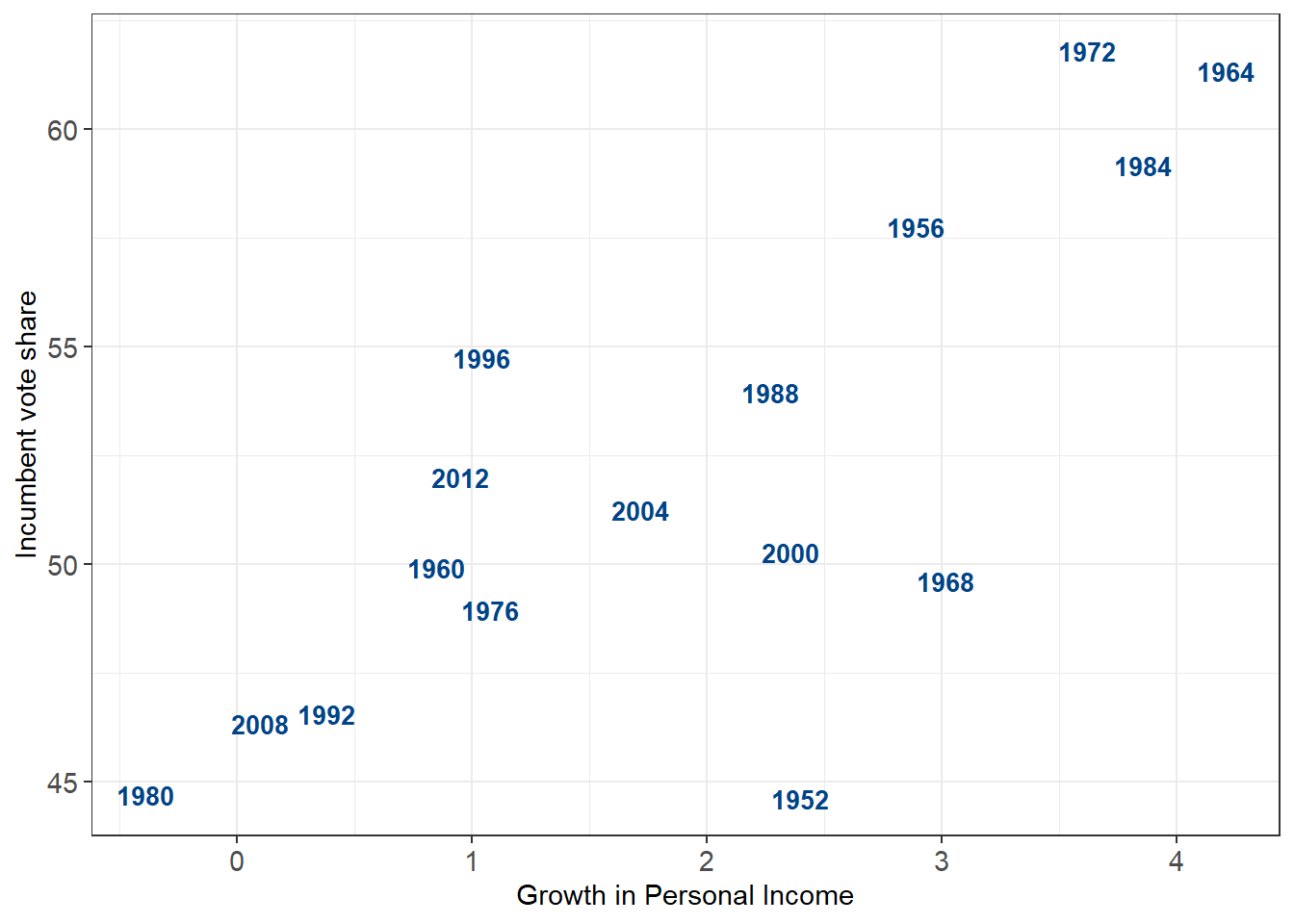

plot1.2 <-

ggplot(election) +

geom_text(aes(x = growth, y = vote, label = year), size = 3.5, fontface = 'bold', color = '#004488') +

labs(x = "Growth in Personal Income", y = "Incumbent vote share") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.text = element_text(size = 11))

plot1.2

# let's regress!

fit2_prior <- c(prior(normal(3, 1), class = 'b'))

# model 1 has default (flat) priors on betas

# 1 percentage point in growth is associated with ~ 3% increase in vote share

fit1 <-

brm(vote ~ growth,

data = election,

family = "gaussian",

file = "hibbs_fit1.Rdata")

tidy(fit1) %>% kable(digits = 2, caption = "Flat prior")

# same model, with much tighter priors

# assuming a mean effect of about 2.5% +- 1.5%

fit2 <-

brm(

vote ~ growth,

data = election,

family = "gaussian",

prior = fit2_prior,

file = "hibbs_fit2.Rdata"

)

tidy(fit2) %>% kable(digits = 2, caption = "Informative prior")

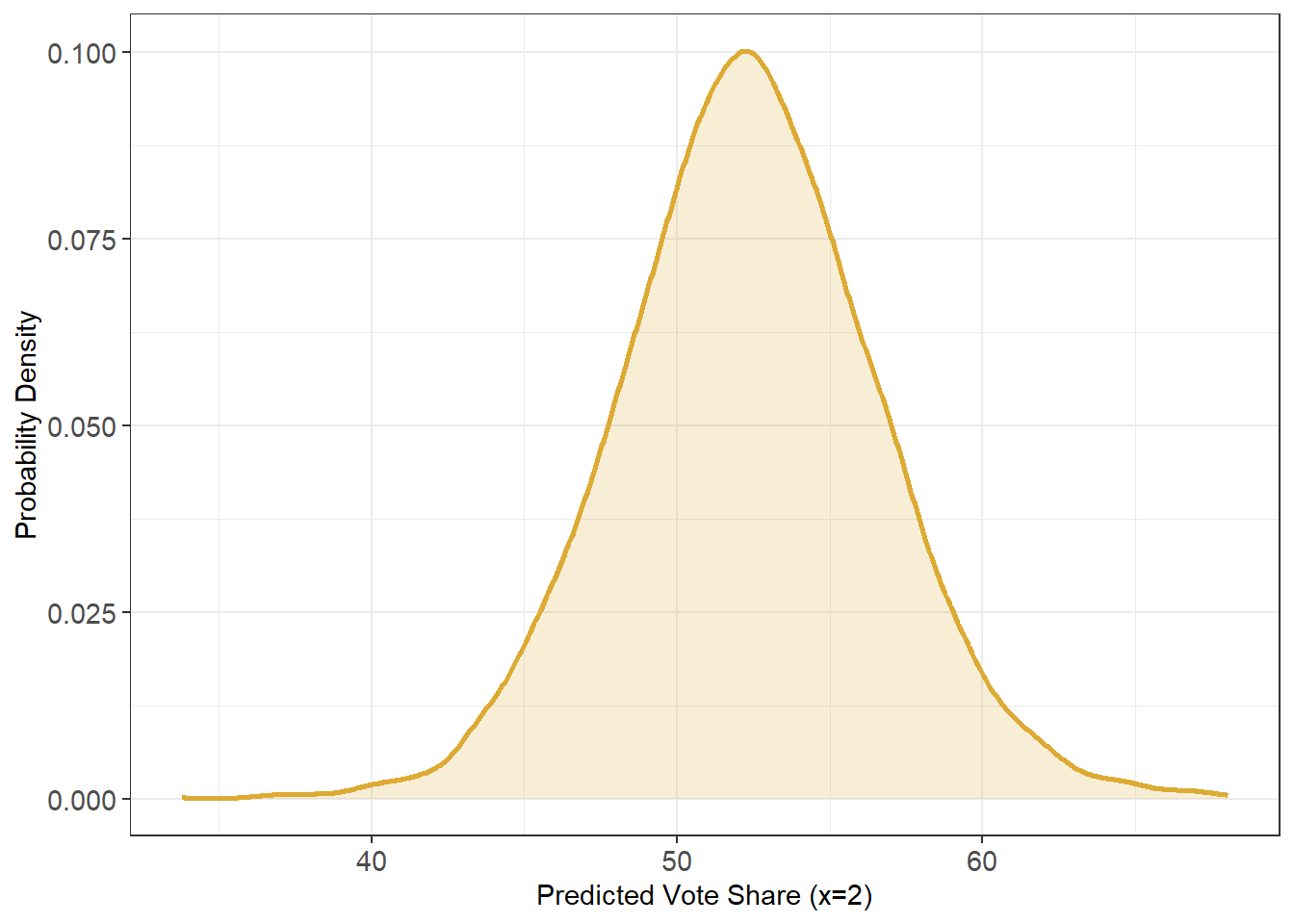

# what is the predicted vote share given a 2% growth rate?

# ~52%, but with a pretty big margin of error

newgrowth = 2.0

newprobs = c(.025, .25, .75, 0.975)

pred1 <- posterior_predict(fit1, newdata = data.frame(growth=newgrowth))

ypred = mean(pred1)

ypred_quantile = quantile(pred1, newprobs)

ggplot(data.frame(x = pred1)) + geom_density(aes(x = x), linewidth = 1, color = '#DDAA33', fill = '#DDAA33', alpha = .2) +

labs(x = "Predicted Vote Share (x=2)", y = "Probability Density") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.text = element_text(size = 11))

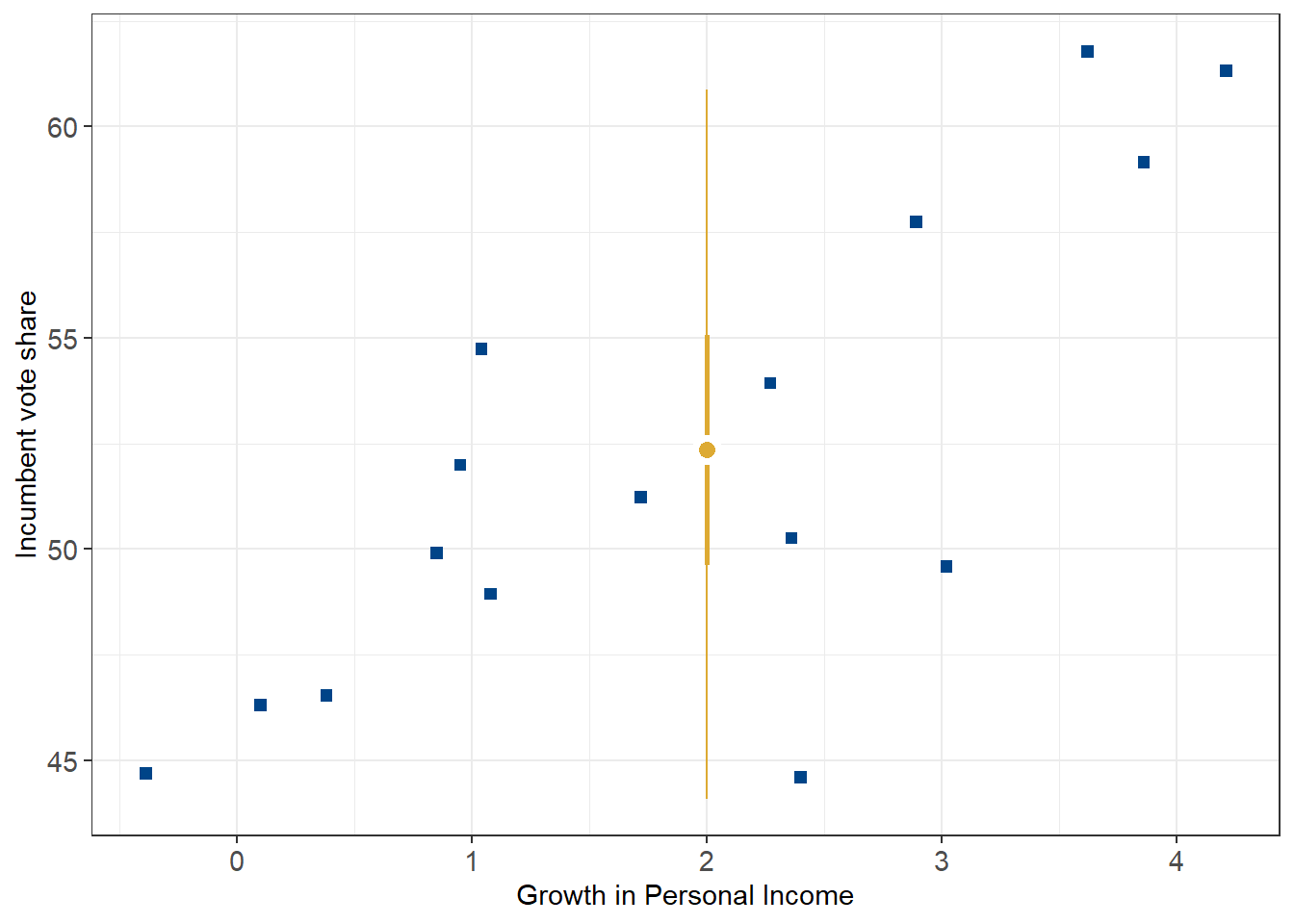

# plot the 50% and 95% credible intervals for the point estimate of 2% growth

plot1.1 +

annotate(geom = "linerange", x = newgrowth, ymin = ypred_quantile[2], ymax = ypred_quantile[3], color = '#DDAA33', linewidth = 1) +

annotate(geom = "linerange", x = newgrowth, ymin = ypred_quantile[1], ymax = ypred_quantile[4], color = '#DDAA33') +

annotate(geom = "point", x = newgrowth, y = ypred, fill = '#DDAA33', color = 'white', stroke = 2, size = 3, shape = 21)

plot_posterior(fit2)